This Gaijin Helped to Produce an Anime Once - Part 2

Or how I stopped worrying and learned to love production committees

Cyberpunk: Edgrunners (2022), produced by CD Projekt Red, Studio Trigger and NETFLIX is one of the most successful international anime collaborations ever made and the winner of the Crunchyroll Anime of the Year award, 2023.

Thanks for bearing with me and waiting for Part 2 to drop. WARNING! This is a fairly long read, but it is worth your time if you’ve ever wondered how to get your story made as an anime in Japan. In the previous issue I had done my part in getting Cannon Busters greenlight and commissioned by Netflix, into production and post, and successfully delivered on time and budget. But! I have never executive produced another anime series since. Part 2 examines how you finance and distribute an anime series production. It ultimately explains why I haven’t done another one since.

What is production finance?

If you watch Cannon Busters on Netflix, linger on the opening credits and you’ll see that there were half a dozen EP credits (“Executive Producer”), which covers the personnel responsible for business and legal affairs, China distribution and gap-financing and film production financing. As you can see. Financing is vital in any television or film production and it is why so many different personalities and companies can be involved. Production finance is unlocked when you have secured pre-sales with key partners in key territories. Either the distributor (Netflix, Crunchyroll, Amazon etc) will cash-flow the production entirely, or you will be entering into a “negative pick-up” agreement, which means that you must mortgage their paper with a lender such as a media fund in order to secure the production cash-flow. The lender is then re-paid when the distributor pays you, the producer on delivery of the finished picture.

My role as EP on Cannon Busters was to be the main responsible party, reporting into Netflix, the production financier and the insurance bonding company on the production’s progress. I am the one who was responsible for ensuring the series was delivered on time and on budget. It’s a high-pressure role, which surprisingly makes you really unpopular. What it did provide me with is a bird’s eye view of how anime is made in Japan. And this gets me to the crux of the matter.

No one in Japan wants your anime!

Before Netflix came on the scene, the best way for gaijin like me to produce anime was to bring my project to Japan as a work-for-hire opportunity. However! Japan’s animation industry is first and foremost creative led and built to service local productions. There are very few Japanese studios who offer service work for international clients and some of those that do shouldn’t because they’re really fucking bad at it. There are much easier and cheaper ways to pay for a nervous breakdown than producing anime.

The other way to make your anime in Japan is by successfully creating your own production committee. According to the excellent ANN encyclopedia, “A Production Committee is a corporation that brings together numerous companies to invest in and co-produce an anime. The rights to the anime, including copyright, are usually held by the production committee (ie: the production committee could be said to "own" the anime).”

Before 2016 and Crunchyroll’s successful foray into the production committee ecosystem, we hardly ever saw non-Japanese companies or personalities included in anime production committees. It hardly ever happened. Ghost in the Shell is a rare exception, and the high watermark for international anime in terms of critical and audience reception and commercial success. Other IP-led projects like The Animatrix (Still one of the best-selling DVD anime releases of all time), and HALO: Legends anthology series utilized a committee structure even though the ultimate ownership of the anime copyright resided with Warner Bros and Microsoft respectively.

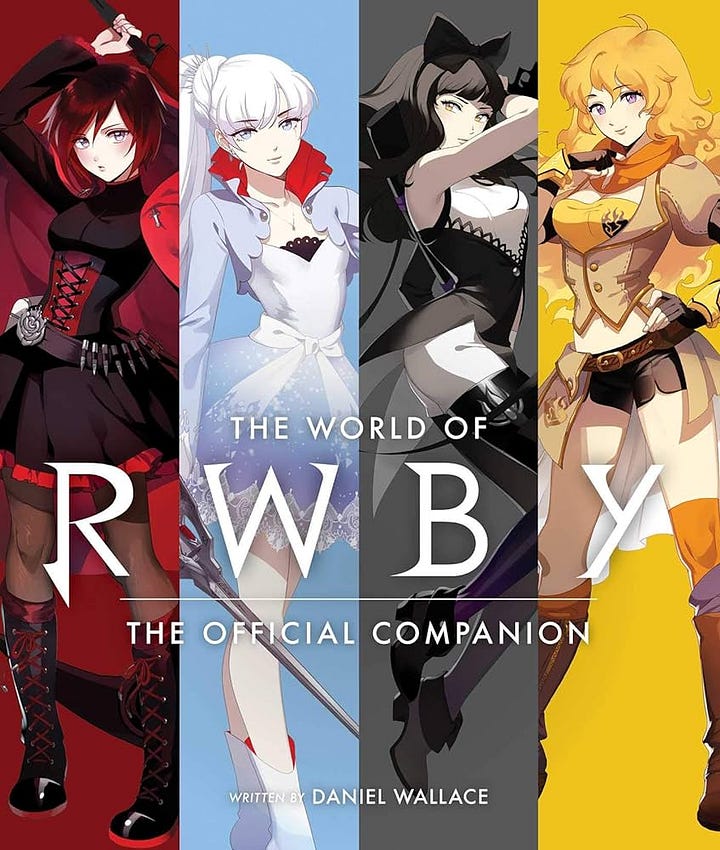

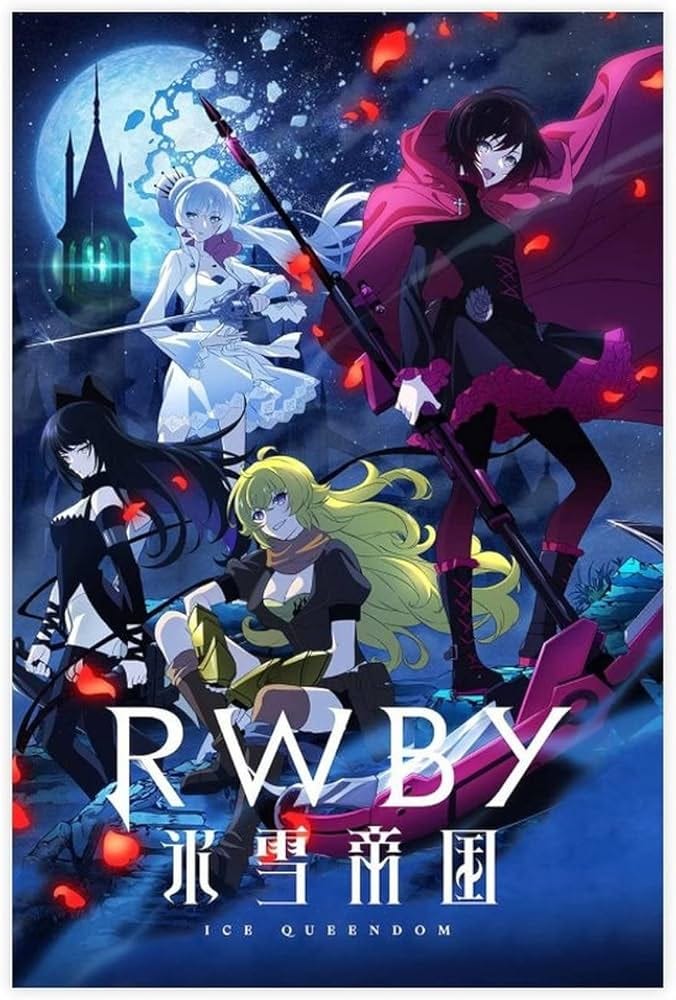

Ultimately! It is the production committees and more specifically, those members who control domestic television broadcast and streaming distribution who determine what gets made, and it is very rare indeed for a Japanese TV broadcaster like Fuji TV or NHK to ever invest in a foreign anime IP. Roosterteeth’s RWBY and Ankama’s Radiant are two notable exceptions. It is worth pointing out that both of these anime are adapted from Japanese-language manga series, themselves spun out of the original American and French originated IP. This is important.

NETFLIX and the international anime bubble

NETFLIX’s unconventional and disruptive fast-scaled growth over the past decade, and its desire to be one of the key global destinations for anime content revolutionized the way anime could be financed, distributed and produced. While they respected the cultural importance of anime as a purely Japanese product their data-led approach to content curation showed them that international “anime-curious” audiences had a much looser definition of what anime is and could be. Despite the huge checkbook Netflix was waving around Tokyo in the early 2010s, very few committees wanted to work with them. It makes sense, because nearly every production committee has a local distributor like TV Tokyo, Fuji TV, TBS or TOHO sitting at its center and providing a large chunk of the investment. They didn’t want or need an upstart American VOD platform coming along, taking their lucrative ratings-winning programming and putting them out of business. So! What did Netflix do?

Netflix went direct to the anime-makers; the studios, the directors and producers and offered them their own lucrative output deals where they would produce anime exclusively for the platform globally. This resulted in a wave of “originals”. Anime based on original screenplays and not based on best-selling manga or light novels, because the other key production committee members are of course the publishers like Shueisha (Owners of Shonen Jump) and they control the most valuable IP. It would take another decade and a bit before they would be ready to produce exclusively for NETFLIX.

In lieu of these blockers NETFLIX set about aggressively acquiring library rights to key anime franchises in key international markets by sublicensing the streaming rights from the local distributors such as Manga UK, Madman Australia, Funimation USA and Selectavision in Spain. They also started looking for international anime series to produce.

Jerome’s Top International Anime Productions

Ghost In The Shell (1995, Manga Entertainment, Kodansha, Production IG)

The Animatrix (2003, Warner Bros)

Halo Legends (2010, Warner Bros)

Afro Samurai (2007, Spike TV, Gonzo, Funimation)

Afro Samurai: Resurrection (2009, Gonzo, Funimation)

Cannon Busters (2019, Netflix, Bilibili)

Yasuke (2021, Netflix)

Scott Pilgrim Takes Off (2023, Netflix)

Pacific Rim: The Black (2021, Netflix)

Cyberpunk: Edgerunners (2022, Netflix)

Tekkonkinkreet (2006, Studio 4C, Dir. Michael Arias)

RWBY: Ice Queendom (Crunchyroll, Tokyo MX, 2022)*

Radiant (2018, NHK, Crunchyroll)*

I’ve provided this shortlist of what I consider to be some of the most commercially successful international anime productions that were actually made in Japan. While at Manga Entertainment, I distributed some of these works in the UK and as such, have a bird’s eye view on how they performed in terms of home video sales (where relevant) and local ancillary sales to broadcast and VOD platforms. In addition, I was privy to the performance data for some of these earlier titles between 2000-2019 for Australasia, Europe and North America thanks to the privileged relationships I had with other distributors in those territories.

If anime is defined as a term that describes “a style of animation that wholly originates from Japan, we can describe international anime as a type of non-Japanese animation that is similar to or inspired by anime that is not made in Japan.” (Thank you, Wikipedia, for this definition).

The argument over what is and what isn’t anime has echoed around chat rooms, college dorms and playgrounds for decades, but now it has become a multibillion-dollar question. The domestic Japanese market still accounts for as much as 50% of annual global anime revenues, which includes streaming and broadcast fees, licensed consumer products, home entertainment, theatrical, brand partnerships, advertising, experiences and events to name a few. In 2022 the combined value of the anime industry globally was estimated to be worth $26.4 Billion. This sum is predicted to triple over the next decade to over $60B by 2032.

Can anime that does not have its provenance in Japan tap into some of this lucrative international business and is domestic distribution in Japan even that important to the success of your anime?

The titles on my shortlist all enjoyed domestic distribution within Japan as well as the rest of the world except in some cases, China. If you are making an anime inspired series or film, or you are actually producing your overseas originated story in Japan as a full-blown anime production (Like Cannon Busters, The Animatrix and Yasuke), your best bet for actually getting domestic distribution in Japan is to either produce your project for Netflix, Amazon or Disney. Mainly because they are buying the project for worldwide distributions excluding mainland China, and they are a production committee of one. There isn’t a local TV or OTT partner at Netflix to block your foreign anime from reaching domestic audiences.

There are only two anime* on my list that received domestic Japanese distribution on actual local broadcast platforms. They are RWBY: Ice Queendom (Tokyo MX) and Radiant (NHK)

Distribution Challenges and Opportunities

March 2022, the world is finally coming out of Lockdown and the worst of the Covid Pandemic is behind us. The nightmare was finally over for many of us, but not for Netflix. Reality started to bite for global streaming platforms and producers alike, and Netflix was the first to shit the bed. Their first ever major loss of subscribers meant the end of their golden run with Wall Street. Money became more expensive to borrow and the analysts decided that their current “spend to grow” strategy had become unsustainable. Suddenly! This darling of Silicon Valley and Wall Street was being asked to do the unthinkable. Become profitable or else!

This affected their anime strategy in a number of ways. Their anime team shrank and it became more Japanese and less international. Funnily enough. Netflix Anime now operates much more like the rest of the domestic channels it competes with. It bids against everyone else to join production committees early in order to secure the Japanese streaming rights, or it bids against international competitors like Crunchyroll, Disney, ADN etc for the exclusive streaming rights for next season’s hits. It even enters into non-exclusive licensing agreements, with local TV broadcasters.

Those anime Netflix does wholly finance and distribute are very Japanese (like Delicious In The Dungeon) and its international anime productions tend to be very high profile and high calibre with creative control for the finished program resting squarely on the shoulders of the creative partner ala Cyberpunk: Edgerunners from the freaking awesome Trigger. Netflix have learned a lot from their first decade as an anime producer. They work smarter and harder on their anime content strategy.

Netflix’s reorganization of its anime program doesn’t mean that shows like Cannon Busters or Yasuke will never be made again by them. They have a whole other team based out of Los Angeles producing “adult-animation”, which includes anime adjacent productions like ARCANE, Blue Eye Samurai and Adi Shankar’s Captain Laserhawk to name a few.

What about Crunchyroll?

Crunchyroll hasn’t had the same growing pains as Netflix. Its global subscriber base is now 13 million and company is reported to have an annual turnover in excess of $1B. It doesn’t operate in Japan or South Korea, but it has expanded into Southeast Asia with India being of specific interest to the Sony owned company.

Crunchyroll has a large Japanese and international team based in Tokyo. Their perseverance and investment, and their acquisition of key Japanese anime production personal from other well-established companies has resulted in a very successful content pipeline. Crunchyroll is very well funded by its parent, Sony Pictures. It is in the enviable position of cornering the global anime streaming market and smart enough to focus singularly on anime and anime audiences. This gives Crunchyroll the unique commercial advantage of being the primary international distribution and rights management partner for nearly half of all annual anime series output from Japan. While costs have increased significantly post-Pandemic, anime is still relatively cheap to acquire compared to live-action, and the global audience is still growing, even while the domestic audience in Japan continues to shrink as audiences age out of the market.

Crunchyroll is now firmly established as a producer of anime within Japan. It sits on hundreds of different anime production committees as the main international partner. It operates a non-official “100% Japan” and “No CG animation” policy. They dare not risk the ire of the global fandom by delivering “inauthentic” anime to them and diluting the provenance of anime as a singular Japanese cultural product. What international anime productions it backs still tend to be very specific regionally as can be seen with their very successful run of Korean Webtoon adaptations.

Crunchyroll’s influence within the Japanese industry cannot be underestimated. Their commitment to distribute anime across the 200 or so territories they control can bring up to 60% of the production budget into the pot. They will continue to have an out-sized influence in determining which anime get made, and which don’t outside of the manga and videogame mega-brands.

For international IP owners and producers, dreaming of making their show in Japan or with Japanese creative partners, the primary question you must ask yourself is this, “Does Japan need this program?” The answer is “It doesn’t”. You need to start thinking out of the box. What types of content do Japanese audiences spend a lot of their time with?

Webtoons is the IP generator for tomorrow’s international anime hits

More and more, Japanese consumers aged 13-25 are spending almost as much time as their overseas counterparts engaging with short-form video content and YouTube. They’re spending even more time on mobile and free-to-play cross-platform video games as well as the big console game releases. But! Most importantly, they’re reading a lot of Webtoons.

Webtoons originated as a new type of digital manga app, primarily for the distribution of Korean comics, commonly referred to as manhwa. Webtoons is becoming a major part of the global pop-culture media mix and is expected to be worth $56.1B by 2030, growing at a CAGR of 36.8% from 2022-2030. Crunchyroll has had a co-production agreement in place with Webtoons since 2019 and it is really beginning to bear fruit for them. Some recent successes include Tower of God, God of High School and most recently, Solo Levelling, which currently sits in their global Top 10 streaming series of Q1 2024.

What is vital to Crunchyroll’s continued success in the production committee ecosystem is its ability to partner with local distributors. Either broadcasters, streamers or producer/distributors like Pony Canyon and Bandai Namco Filmworks. In order to bring them on board a Crunchyroll-originated production I believe it must be able to provide these domestic partners with an opportunity that is super-relevant to their audiences. Hence their pivot into manhwa and Webtoons adaptations. Japanese audiences love this content, and they know it.

If you can’t beat them. Join them.

Ellipse Animation, the French kids and family production studio responsible for such hits as The Smurfs and Babar has experienced a tough year or two, as demand from global streamers for kids’ content has contracted. One ray of sunshine in their annual earnings report is “adult animation”, which their CEO described as facing robust demand globally. They also recently announced the establish meant of their own webtoon studio to develop and publish partner’s and their own IP. They won’t just be launching their titles in French. They’ll be launching in English and Korean to name a few. This to me feels like one of the smartest ways to incubate and develop IP as an outsider that will connect with Asian audiences, build brand awareness and hopefully, develop audiences in Japan and elsewhere for the eventual anime adaptations.

Pivoting to webtoons is not the panacea for achieving your dream of making an anime series. But! Best practices as established by industry leaders like Crunchyroll and its partners in Japan and Korea suggests a way forward for ever closer collaboration between international storytellers and Japanese artists. I can’t help thinking that as the Japanese audience ages out of the Japanese pop-culture market (A rather stark concept considering what this term means when considering Japan’s demographic crisis), their domestic audience will continue to shrink and their reliance on the overseas business will necessitate a creative recalibration of the type of productions they make.

I agree that anime is a specifically Japanese cultural product. I didn’t used to think this way. Nonetheless. It is disappointing to me, as someone who showed that you can, as a non-Japanese team with a non-Japanese IP make an anime series entirely in Japan with 99% Japanese crew and staff, that the worlds most important distribution platform for anime defines itself by the barriers it places in front of storytellers rather than the bridges it builds for them to connect with other storytellers and a diverse global audience. But! Hey! You know? They make video blogs about how to cosplay with Afro hair, so I guess that’s one way to show the audience you see them.

On The Verge's Decoder podcast last week, Crunchyroll president Rahul Purini said, "The way we think about anime, we believe it is something that is conceived and / or created in Japan." This is probably confirmation that the "100% Japan" policy has become very much official.

https://www.theverge.com/2024/2/26/24081180/crunchyroll-president-purini-anime-funimation-shutdown-sony-merger-decoder-interview

You make a good point that RWBY and Radiant aren't direct adaptations of foreign IPs. This nuance is probably lost to most viewers, but important in the business context. I was reading a recent interview with the head of French publisher Ki-oon's Japan branch office, and she also sees manga as a pathway to getting foreign IPs adapted into anime.

https://teller.jp/borderless/49/